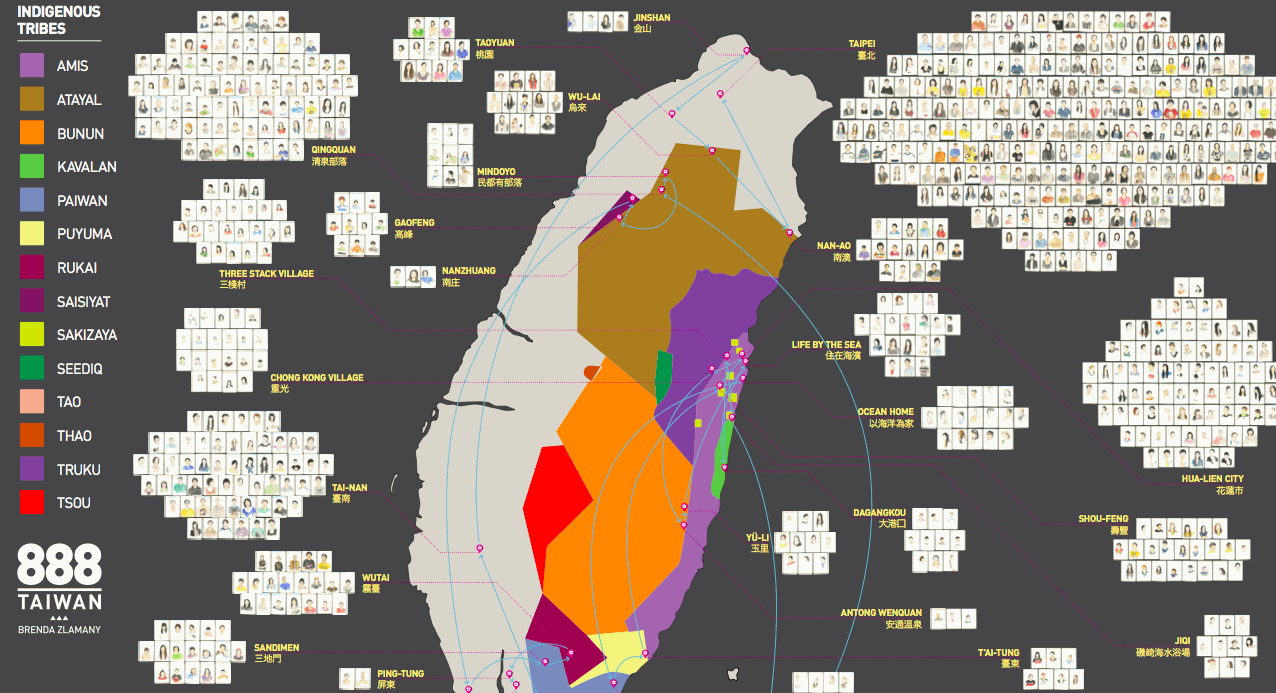

Image courtesy of Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany is a NYC based artist focusing on a multiyear project exploring the effects of portraiture in communities, from aboriginal villages, to the UAE, all around the world. In the digital era, Zlamany is taking account of the social connection between artist and subject in real life conversations raising the importance of social understanding about the communities we live in and how they are portrayed.

She has shown in the United States, Europe, Asia and the Middle East at institutions including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei; the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution; the National Museum, Gdansk; and Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent. Her work has been reviewed in Artforum, Art in America, Flash Art, the New Yorker, the New York Times, and elsewhere and is held in the collections of the Cincinnati Art Museum; Deutsche Bank; the Museum of Modern Art, Houston; the Neuberger Museum; the Virginia Museum of Fine Art; the World Bank and Yale University.

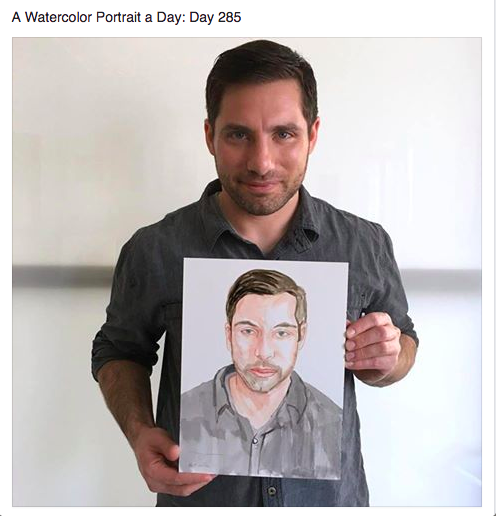

This conversation was done while Brenda painted my portrait in her Williamsburg studio.

Brenda: So, let’s have a look at you. Let me see different sides. I’m thinking you’re frontal. Are you thinking you’re frontal?

Brett: This is my better side.

Brenda: Why is that your better side?

Brett: I don’t know – perhaps it has something to do with the way my hair grows.

Brenda: Some people feel they have a better side. Others say, “What are you talking about?”. You look like you would be good frontal, although I do agree that that is your better side. This is the deal. If you are very still while I draw you with the camera lucida, which will take under two minutes, then I’ll redraw you from observation and then you have total flexibility; you can move around, you could talk, you could get up, but if you’re not still and the drawing is not good, that means I’m going to be correcting and if I’m correcting in the painting, then you’re not going to have as much freedom to get out of the pose.

Now, I’m going to redraw you from observation. So, you can talk - I’ll tell you what I’m looking. Just stay in the pose, if you don’t mind.

Brett: I’m very comfortable, so it’s perfect.

Two minutes of drawing pass.

Brenda: I actually think the drawing is pretty good, but the thing about the Camera Lucida is it really distorts. I was actually moving it around while I was drawing you to make up for the distortion because I know what the distortion is going to be, but I still have to correct even with the moving.

Brett: Where did you get this tool?

Brenda: Well, actually, I got it when David Hockney got his. I was in his studio with his printer, Maurice Payne and Maurice gave me one. This was in late 80’s, I think.

Brett: What was your origin in art?

Brenda: I was one of those kids who was always an artist. Were you that kind, also?

Brett: Just about. When I was around 13 year old, I saw Matisse paintings and I was hooked.

Brenda: I think I was even earlier than that and I think it may have come from my own deficiencies. You can see I’ve got this mirror that I’m working with now. I was a mirror writer as a kid, and so reading and writing came very late to me and I was left-handed in a Catholic School where being left-handed was sinister, so there was a lot of discrimination, but the one thing I could do was I could draw. So I was the one who got to decorate the church. Drawing was the only thing I could do well. And, actually, the real truth is when I was in first grade, the nuns came around and they said, “What do you want to be?” and I said, “Oh, I want to be a nun,” and they said, “No way, you’re left-handed.” So then I was, “Okay, I’ll be an astronaut,” and they said, “No, you can’t do that, that’s only for boys.” So, being a painter was the next thing I said- so this was actually my third choice of career, but it’s not a bad choice. I don’t think I would’ve been a great nun, to be honest with you.

Brett: I’m also left-handed and I also went to Catholic School.

Brenda: But you’re probably younger than me, so they probably weren’t allowed to beat you if you were left-handed. I’m sure they tried to train you out of being left-handed, but they did it in more subtle ways in your day, right?

Brett: They never had desks for left handed kids. I recall being asked me if I wanted to become a priest.

Brenda: A left-handed priest?

Brett: I said, “I think I’m going down a different path,” and then I went to art school after that, basically.

Brenda: This is going to be cool. It’s going okay ( talking about the portrait in progress). To me, these portraits are about trying to come up with an image while the person’s sitting there that tells you what I think of them and what’s going on between us. So, it may not be a photographic likeness, but it might be more like them in another sense. I found that since I started this project - if I have to do a portrait from photos for an oil painting, it’s useful for me to have done a Camera Lucida watercolor portrait, so I could figure out what’s important because photography doesn’t really tell you what’s important. It tells you everything!

But it’s also true that the better you are at portraiture, the more you can look at a photo and figure out what’s important, because the photo gives you too much information and it’s not even how you see people because you can’t see all of that at once. I was in a self-portrait show (at Bravin Lee Projects) and I was talking to the gallerist recently about how in these watercolors I have to figure out what the 10 most important things are about a face because maybe that’s all I can address in 30 minutes.

Brett: And when did you start the Lucida project?

Brenda: Well, I had a Fulbright - so, what happened was I got the Camera Lucida when David got his and he did his experimenting and he wrote his book which I’m sure you’ve seen and mine just got put away. Then I wanted to do a portrait project overseas. I’d been in Tibet with my daughter and I was taking all these photos of Nomads, but then I came home and I painted a bunch of paintings and I found it really deeply unsatisfying because, for me, when painting portraits there is a component where the subject confronts the image and it’s something that makes it more exciting. There has to be an audience that’s inside - it’s the subject or someone related to the subject that I’m sort of coming up against. And, I knew that I would never see these people again, so I was thinking, “How could I do this?”. But, some of the discoveries that I made on the trip to Tibet about the gaze of people who are not used to looking in mirrors because, I was painting Nomads who don’t really carry around mirrors. You could see this gaze in the photos and I explored it in the paintings. So I decided to write a Fulbright to Taiwan because there is an aboriginal population that lives outside of mainstream culture and I thought, “Well, why don’t I go there and use the Camera Lucida, and that way people will see me painting them and that way, even if they never see the oil paintings that I make later, I’ll have had a discourse which will make it more satisfying for me.” So that’s what I did.

My daughter is a fluent Mandarin speaker, so the other criteria for the Fulbright was that it took place in a Mandarin-speaking country because she would be the interpreter for the project.

Portrait #124 (Young Man from Sandiman [Paiwan]), 2012. Oil on panel, 21 x 14 in. Image courtesy of Brenda Zlamany.

Brett: What are the rules you’ve established on the project today?

Brenda: Well, I’m aiming for a year, so that’s 365 portraits. One a day. But I don’t have to do one a day, if I do two in a day, I get the next day off. I’m the one who makes the rules, so I made that rule because sometimes people show up as a couple or they’re from out of town and they’ve got a kid and it occurred to me that I can’t say, “Okay, I’ll do you now and you come back tomorrow.” So, as long as I’m posting one a day and I’m posting them in the order that they occur, it works. I can’t go and take an old portrait from the past, if I missed today. So as long as I’m staying up with the time and posting them in order, I’m within my rules. And then, among the other rules is that I can’t touch the painting after the subject leaves, so, basically, what I get is what I can see when I’m with you.

So, I think your head is drifting down a tiny tad, but it’s still great. Okay, good.

Brett: How has the work changed while you travel?

Brenda: I’ve actually done some of my best work out of town. I mean, it travels really well because I set it up as a Fulbright project - I went to 33 villages and painted 888 people, that was a huge number. When I wrote the Fulbright proposal, I didn’t even know how use the camera lucida. I just practiced for one week before I left. And I thought, “Okay.” So I came back knowing how to do it, but of course I was mostly painting Asian people, and it was a whole new thing learning how to paint Caucasians because it’s a much bigger nose, usually.

Brett: What number is this?

Brenda: I believe you’re 284 or 285. I’m coming to the end of the year. There’s a part of me that wants to go to 1000 because there’s just so many people - the thing is I’ve been in the art world for 30 years now and I just know so many people. And I know that as I get closer to finishing, I’m going to start feeling like, “Oh my God, what about so and so? Can I just include one more?” So, I mean, I keep saying I’m going to stop in a year and my daughter really hates the project because she hates having people in our house constantly, but and then there are times when I feel I can’t take it anymore and I’m just not in the mood to paint somebody, so I could see advantages for the project being over.

Brett: And it’s more than painting. It’s performative.

Brenda: Yeah, it’s a performance.

Brett: Seeing this is performative, are you more introverted or extroverted?

Brenda: I’m more of an introvert. For me, painting portraits is the kind of socializing that I really like to do. I’m not introverted when I’m painting. And I actually feel like the connections that I make with people when I’m painting them are much more rewarding than in real life. I would rather be painting you than having lunch with you. And after I paint you, I’m going to feel more connected to you. I was at an opening recently and I had painted at least half, if not two thirds, of the people in the room. I felt I was really entrenched in people that I loved - my family - whereas before I painted these people, even though I’ve known them for 30 years and they’ve been in my world, I didn’t feel quite so close.

Brett: Does it feel therapeutic? How so?

Brenda: For everybody. It’s actually been great - in so many ways, it’s been great for me, but the biggest way is that it helped me be more social, when as a single parent, I had not been going out that much.

Yeah, and I don’t have any support. Her dad wasn’t on board to help and we don’t have any family that is involved, so being a single parent was very, very isolating. But this project has been really social and great. I’m from New York and then I went away to college, and then I came back in ’81, after I graduated. And then, my daughter was born in 2000 and - I mean, the only thing that really changed was I had to become more businesslike. I’ve been supporting myself from my paintings since maybe ’85, so I didn’t paint less because that’s how I paid the bills, but I socialized less. I became kind of isolated in some ways. But now she’s getting older and the portrait project is getting me back into my social world. And it’s getting me back in a way that’s really interesting because people I haven’t seen much of, who haven’t been over, sit down, we talk, we have a studio visit, they tell me what they are doing and it makes really deep connections, deeper than just bumping into people at openings. So it’s been really, really nice. But that was not part of what was intended in the project. It’s just sort of what happened.

“888” documents Brenda Zlamany’s project “Creating a Portraiture of the Indigenous Inhabitants of Taiwan.” From July 1 to September 30, 2011, supported by a Fulbright grant, Brenda traveled in Taiwan, primarily to aboriginal villages. Image courtesy of Brenda Zlamany.

Brett: How do you exhibit this work?

Brenda: After I did the project in Taiwan, I realized the drawings were not the end game - the end game is how it’s presented. There are photos, there are drawings and there is data about the experience and what happened. And so, I did a show at MoCA Taipei and it was - after I did the Fulbright and did the watercolors, I went back to Taiwan with another grant to do the show and we spent two months making a digital presentation that involved two movies, a digital sketch book that told stories about the subjects when you swiped the screen to turn the pages, an installation with photos and tribal music, a map charting the journey that showed each of the 888 portraits, a digital wall of 100 subjects signing their portraits and the watercolor portraits. Then I brought the show back to New York and it was shown in the Taipei Economic Culture Office, on 42nd Street, and I could barely get anyone from the art world interested in the show. Even though it was ten blocks from Chelsea, I got tons of Chinese Press but I could not get any American critics to really take it seriously and, I think, it was partially because Americans are really not interested in other people that much, certainly not Taiwan’s aboriginals. So, I just sort of went back to my normal everyday work and I just thought, “Oh, that’s too bad,” because I had actually come up with this whole concept of traveling around the world and doing this project, because it’s kind of a diplomatic project of building communities and I actually did it in Abu Dhabi, also. So, then, I just said, “Oh, that’s too bad,” and I went back to my regular work. I continued to do it, but I thought, “Okay, this is not something I’ll be showing, here. I’ll just show it in the countries where I do it.” And then I went to this thing - do you know Paul D’Agostino?

Brett: Yes. Who doesn't know Paul?

Brenda: Well, I went over to Centotto to check out this thing that he does. And I brought along Camera Lucida drawings from Taiwan, Abu Dhabi and from the Supernormal Festival. By then I had done it at an experimental music and art festival in England, as a workshop, and everybody really, really dug them and it occurred to me that maybe I was selling myself short; that maybe these drawings are okay and I just didn’t pick the right population.

Then I got a commission to paint Yale’s first seven women PHDs and I just said, “Oh, well, I’m going to spend six months painting these women from the late 19th century and it’s going to be really isolating, painting dead women.” So I just thought, “Well, why don’t I have a parallel project where every day I paint a live person alongside?” Since I am painting the watercolor portraits in my studio, I get to see how people are reacting to the project, because that project - the Yale Project, was really, really hard. It’s a public project and it was just really interesting to me to have people come in every day and tell me what they saw. It was useful for the Yale Project and it was also useful for keeping me balanced, from going too much into the world of the dead because these women had such a strong pull. And then, I started noticing that when I posted them on Facebook a little community of people was forming, who expected to see them each day and critiqued them. It sort of took its own momentum and that was really interesting and fun for me.

Brett: It was interesting that the project is so intimate, but a lot of people interact with the project on a digital basis.

Brenda: When I run into people, they’ll say to me, “I look forward to it every day,” I painted this woman named Andrea Belag, the other day, and she said, “You know, when I see my friends, I don’t see how they look, I see how you painted them.” Not that I’m comparing myself to Picasso, but when I think of Gertrude Stein, I think - what do you think of when you think of Gertrude Stein?

Brett: The famous Picasso portrait.

Brenda: Yeah, even though we’ve seen photos of her - I’ve seen plenty of photos of her. So that’s not about me trying to be Picasso. But what it tells you is that something about the subjective image, the painted image has more in it than the photograph.

Brett: Do you consider the work participatory and if so, how?

Brenda: Yeah. I actually have the subject sign them too. And, there are things going on that you don’t know about. Some of them I can tell you because I know what they are and some of them I can’t tell you because they’re unconscious. I’ll give you an example of one that is not about you. Let’s say someone was balding and concerned about losing his or her hair and I was getting around to the hair area. I would see an expression on their face, possibly, that would tell me that I’m in the danger zone, and I may give an extra stroke of hair and I could then notice that they look happy. And so, the subject informs me because they are looking at the painting as it happens.

And there are times when people will say, “It doesn’t look me,” and then I’ll photograph them with it and I’ll say, “It looks exactly like you,” and they’ll say, “Oh, wow, it really does.” sometimes, we don’t realize how good the likeness is until we actually see it against the photo.

I so much appreciate that you’re trusting me because I can do anything and it’s going to be on Facebook in two hours and that’s another one of the rules - there are no rejects. , even if it sucks and I know it sucks, it’s going on anyway.

Brett: How do you find subjects? We met through a warm introduction (via Austin Thomas) so the trust is there.

Brenda: I would say maybe two thirds to three quarters are people I know. And, if I’m running a little low, all I have to do is go out to an opening and boom, I have more subjects to paint.

Brett: Have you painted visitors? I’m thinking of Van Gogh’s “Postman.”

Brenda: Yeah, I’ve done the “Postman”, I’ve done the “UPS Guy”, but he made me not show his face in the Facebook photo because he’s at work. And, the uniform has a copyright and he is not allowed to - isn’t that interesting. I’ve done the guy AAA, who came to fix my car. I’ve done anybody - I’ve done roofers - anyone who comes in here who’s willing is fair game.

Brett: Do you find that there’s a difference between the people who are in the art world that may be more familiar with art and techniques?

Brenda: Yes, I mean - many people in the art world are professional posers. People who are in the art world are better at controlling how they’re seen than people right off the street.

Brett: So, would you say there’s a tinge of branding to us in the art world (we’re aware of visual presentation)? After all, many of use spent years learning the foundations of drawing through countless self-portraits in art school.

Brenda: Yeah, and, I think, people think carefully when they come over, about how are they going to be seen. Absolutely. Sometimes people will contact me and they’ll say, “Okay, how should I be?” And I’ll say that there’s no right and no wrong, it’s how you want to be seen. Some people do wear costumes - somebody showed up with a hat and a hatbox and it was this extremely specific Sargent kind of hat. This woman came over, named Julie Torres.

Brett: I know Julie, yeah.

Brenda: And she was wearing her Pussy Power T-shirt and it was really nice. So I said to her, “Well, this is really confusing for me because you have a great face and I want to come in and do a close-up with your face, but this is an awesome T-shirt. So if I do the T-shirt, I’m going to have to pull back and this is going to be about the T-shirt more than it is about your face. We decided that the T-shirt was great and could be an important part of the portrait. And people loved it and she was hugely, hugely popular and, I think, the person who made the T-shirt got some nice attention.

Brett: Julie is so generous like that.

Brett: How are you choosing subjects?

Brenda: I’m not picking them based on their fame. I’m picking them because these are the real people in my real world and there are a lot of them and they do the work every day and, I think, they deserve the attention, actually.

Brett: What do you think of Chuck Close’s famous quote, “Inspiration is for amateurs, the rest of us just get to work"?

Brenda: Yeah, I get what he’s saying. I know where he’s coming from. What he’s saying is - and I’m definitely on board for with that - I mean, I’ve been painting for so long and painting every day for so long, since I was - because I went to art school starting when I was 13. So I haven’t - and I don’t think I’ve ever had, - I mean, the longest I’ve had off was two months when I was on bed rest for the pregnancy, but then I learned how to knit, so that was somewhat creative. But, yeah, there are times when I step back and I reconsider the project and look for inspiration.

But, basically, one day leads to the next. There are times when I, after a show sometimes, go on a residency or something like that because I want to shake it up or with the Fulbright, I wanted to see, “Is there another gaze other than the narcissistic sort of western gaze that we’re accustomed to? Is there a gaze of someone who’s looking more internally?” And so, I was looking to find that gaze.

Maybe I’m not trying to uncover something because I actually don’t believe you can ever know anybody. For instance, I think in reality, you don’t even know your wife; you just think you know your wife. When my grandfather died, this woman who we had never seen, came to the wake and kissed him on the forehead and then left and we all wondered, “So, who was Francesco?” We don’t know who he really was because who was this woman? But, I think, what you’re trying to get out of a portrait is you look at the sitter and a story occurs and this is what you’re going to go with, this is how you see them. And whether or not it’s accurate, I don’t know even know if there is an accurate seeing, is not important. I’ve had people, a particular artist that I painted in the late 90’s, who he took his portrait to his therapist because he felt that, whatever it was, I got it in the painting. (ARE we ok to publish this part)? Yes, took out the name

He felt that that was what he was trying to get out in the therapy but he couldn’t get there. So he was like, “She got it. Let’s go from this portrait,” so I said, “Go ahead, take it with you.” So he took it but I don’t know if it was successful.

Brett: There is the old tradition of courtroom sketching. Do you think about that at all?

Brenda: Yeah, they’re great, right? I mean, I’ve never really thought about them, but that’s really interesting. Yeah, what is the training to do that job? But wouldn’t it be fun to get to do that? I would love try that job. Somebody should do a show of those drawings.

Brett: It’s a whole another interview. We’ll have to do an interview of a courtroom sketcher.

Brenda: It’s interesting that you brought it up because I’ve never heard anyone bring that up. Who are they and are there any of them that also have an art career?

Brett: There’s that recent show on Netflix, “Making a Murderer”. There was a portrait drawn by a police sketch artist that looked like the accused person and it led to him being falsely accused and spending 17 years in prison before the actual killer was identified by DNA.

Brenda: I mean, I don’t know if this is related, but I think that things can be uncovered in drawings that cannot be seen otherwise. And I’m going to give you an example of a commissioned portrait I did for Jonathan O’Hara’s family - do you know the art dealer, Jonathan O’Hara? He was my dealer and I was doing a big commissioned portrait, a seven-foot portrait of the three kids, the two cats, the wife and him. And the wife was miserable during the whole thing and she kept telling me to repaint her face, “I look unhappy.” And no matter what, I could not get her to look happy and then, guess what happened when the painting was finished. They got divorced. The painting took about six months to paint and by the time it was done, the relationship was over. It was just unfolding. In the painting I was able to see something that they, themselves, couldn’t see yet, so that was really, really interesting.

In the shorter paintings, other things happen. People come with an agenda other than the agenda to be painted. I would say a certain percentage of people come and they’re just coming here to be painted and I just think that’s so great. But then there are people who are coming for other reasons and I can’t even say - it’s impossible for me to say what the reasons are because they are so complicated. But what I can say is a certain percentage of people cry during the process of getting painted because they tell me something so painful.

I actually even had someone who had killed in a war situation and we were talking about Heaven and Hell and whether or not he, with that level of blood on his hands, you know….

And I’ve painted a lot of people who are aging because my demographic is 45 to 70. And, I’ve learned a lot about beauty, you know, loss of beauty, different kinds of beauty - that’s been one of the things that’s really interesting for me. And I’ve learned to see beauty differently because we’re so programmed to see beauty in a certain way in the culture.

Brett: Do you feel that this project has made you more compassionate?

Brenda: It has, yeah. It’s made me feel that I love people more; I feel more empathy for different kinds of artists and their struggles. I feel more generous with what kind of art interests me because I sat down with the makers of things and I understand their projects better, I understand their intent and their seriousness and the sacrifices that they’ve made. So many artists I painted are getting very little reward and they’re completely devoting their lives and it’s fascinating. There’s a huge population of people who are just, you know, are self-driven.

Brett: Are their some unique qualities about the world today coming out in the portraits?

Brenda: Well, I mean, one of the things I'm noticing in my experience with the portraits is social media’s working differently and that’s making it a different art world and I think it’s great. We’re in a point now where – I mean, it used to be when I first came to New York, when I was 20, you needed to capture the eye of certain critics or you just simply would not get seen. And now you can build a whole, entire life on social media. And some of those critics actually are on social media. And if they didn’t see your show and there’s a lot of talk about it and buzz, they’re going to have to look.

Brenda: I'm just going to work a little bit more on your facial hair, but I'm pretty much done. I could stop at any time, but let me get a little bit more on the facial hair. I’ve got you pretty introspective. I mean, you definitely have a very interior gaze in this picture. So, what’s going on behind that?

Brett: I'm introspective at times. What is your next play? (project)?

Brenda: I’ve just curated a show called ‘the Conference of the Birds’ which is scheduled to open on May 18. I’ve gotten so addicted to painting these portraits that I am worried I’ll crash when the project is completed and it’s a doubly dangerous situation because the Yale portrait will be unveiled at about the same time that the ‘Watercolor Portrait a Day’ project is finished. So there definitely is a big empty space on the horizon. But I’m safe because balancing the egos of 36 artists and installing such a diverse group off works should be pretty all encompassing. I’ll also need to paint a few birds for the show.

Brenda’s portrait of me completed during this interview. 2016. Image courtesy of Brenda Zlamany.

![Portrait #124 (Young Man from Sandiman [Paiwan]), 2012. Oil on panel, 21 x 14 in. Image courtesy of Brenda Zlamany.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f19317e4b07aba54d1204b/1468267294821-MBIO1IT8HSQY2XJB1NI4/image-asset.png)