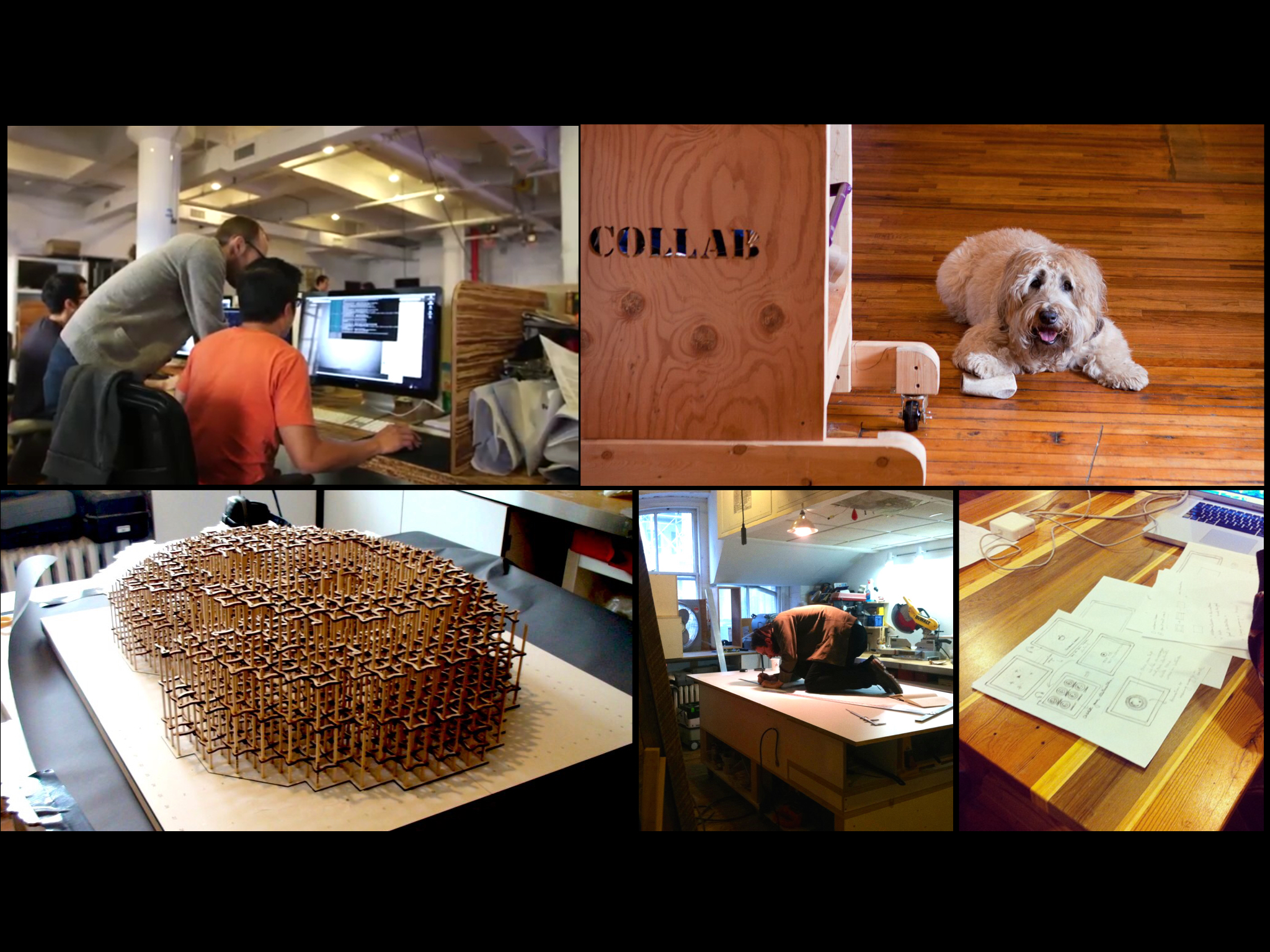

Marc and Adina Levin are the co-founders of Collab, a Fabrication Lab and Innovation Studio in New York City that provides space and shared resources to creative entrepreneurs. Collab is known for its vibrant community of 21st century creatives with skill sets that cross a wide range of disciplines --from Architects to Bio-Engineers to Technologists -- who work on their own endeavors and then collectively on much larger projects, collaborating to bring ambitious experiential work from their imaginations to real life.

We sat down to discuss some of the imaginative projects their community works on and what can be learned from how they work.

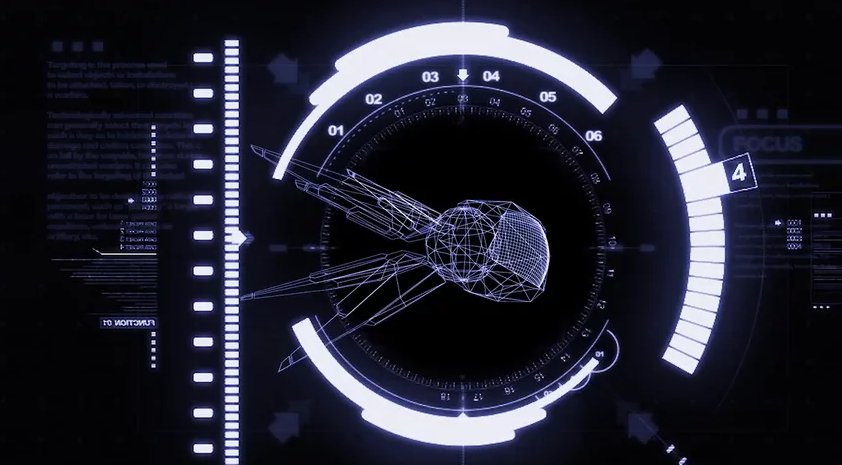

Brazilian multi-sensory ride development. Photo courtesy: Sensorama

Brett Wallace: How do you define Collab?

Adina Levin: I would say Collab is a community of people who share similar ideals yet have widely different sets of talents, skills and pursuits. The unifying theme is that even though we are all working on our own projects, we trust one another and are open to work together. I would summarize it as a community of like-minded individuals with very different, yet complementary skill sets.

Marc Levin: On paper, Collab is a Fabrication Lab and Innovation Studio. But obviously it’s more than that. It’s not easy to define. We have fabrication equipment, and a wood shop, a large open communal space to test, prototype, and assemble in, that sort of thing. But the way we curate the community, slowly assembling a group of people who spend day after day, week and week, month after month with one another in the space, that combination allows for collaboration, invention, innovation and a powerful brain trust. As Adina said, everyone at Collab works on their own projects. But having this talent pool under one roof allows us to join forces as one entity and work on larger projects for our clients.

Photo courtesy of Collab

AL: Collab is also a space where individual members who didn’t necessarily know one another before joining have formed companies. We’ve also been incubating and accelerating companies. That’s definitely one of the parts of Collab Marc and I are most happy about -- we’ve incubated and mentored 9 companies that have launched out of the space and now have a combined valuation in excess of $700 million, and have created more than 300 new jobs. That’s out of a space that’s only 5,500 square feet.

ML: We’re very happy about it. It’s the reason Adina and I are putting together a fund. So members at Collab can have access to money without having to go outside of Collab.

AL: We’re in a unique situation at Collab. Because we work there, we’re able to witness the strengths and weakness of the start-ups in the space. I don’t think money makes a company, but there is a moment when funding becomes necessary to grow. This part of Collab, this incubation side, has been happening organically for years – as I said, we’ve had some very successful companies start and grow and graduate from Collab. Ayah Bdeir launched little Bits out of Collab. When she moved in, it was just herself and one other person. We witnessed Ayah go through the early stages, struggle with early stage issues, and grow her company. We watched her fundraise. Seeing her struggle to get funding was frustrating to us since we’d seen so many companies with less abilities and potential raise lots of money. It was very clear to us from the beginning that Ayah had a brilliant idea. As we watched her work, we saw she also had the perfect amount of intellect, grit and talent to succeed. She hired great people with those same attributes. We thought that investors, who only saw the difficulties in what Ayah was building, without being able to watch her and her team work, couldn’t see the huge potential. If we had a fund in place back then, we could have made the investment into her company and saved her a lot of time and energy. By the way, from two people, she now has more than 125 people and has raised more than 60 million dollars.

I see this all the time with startups. They spend so much time raising money, they get pulled away from raising their business. It is kind of a catch-22. That’s why, as I said, we’re putting together a fund. We’re in a position to witness and gauge which ideas and founders are good investments.

The Little Bits studio at Collab. Photo courtesy: Collab

BW: How did you both get involved in creative fabrication?

AL: Marc and I started about 16 years ago, designing and manufacturing all kinds of products for companies, producing events, doing a lot of production and manufacturing work. Almost immediately, we realized we could be more creative and distinguish ourselves by increasing our capabilities. So we set up relationships with manufacturers overseas. We set up an office in Hong Kong.

Since our inception, we’ve been successful at working with large companies and creating products for them. Clients would come to us with design problems and we would solve the problem and manufacture the goods. During those years, we learned about different processes as well as the disconnect between the people who are designing goods, packaging, clothing, and the manufacturing process. Most designers have very little or no awareness of how their designs translate into a physical object. This disconnect started Marc and me thinking about ways of combining ideas, design, rapid prototyping and fabrication under one roof. The idea for an integrated space had been brewing for some years. When the economy collapsed, we decided it was the right time for us to start Collab. We had seen the positivity and inventiveness that comes from sharing resources - we knew it worked well and figured the economic collapse was a good time to put the benefits of sharing into a community space.

BW: How and when did you start up the space?

ML: We started Collab in 2009. As Adina just said, we had been talking about a space like Collab for years. We thought a space where people could share equipment and tools, their ideas, would be powerful -- a sort of micro-community that could act as a support system against the challenges of being a freelancer. The opportunity to start Collab in 2009 existed partly because of the economic collapse. At that moment, people needed one another. Adina and I were willing to take the initial risk. We took an SBA loan, found a space, built it out, bought equipment, and started Collab. It wasn’t that easy, but that’s what basically happened.

BW: What is the culture like?

AL: It’s as supportive and connected a community as I could have hoped for when we started. I think it’s interesting, because when we started Collab, we went into it with an exploratory mindset. We had a general idea of what we wanted to create, but we let the space dictate itself. I think that’s why Collab is constantly evolving. I think the constant evolution is its culture. Sometimes it is a bit overwhelming. But I think true innovation is overwhelming. You’re always doing something that’s a bit over your head. It can be uncomfortable, but to be overwhelmed is necessary. It is the only way I know to be truly innovative, to push forward with big ideas. It has to happen with people you trust. That is super important. I think that’s the essence and the spirit of Collab. It’s the brain trust. It’s the safe environment. I don’t know if a brain trust qualifies as culture, but having a neuroscientist sitting next to an architect sitting next to a fabricator sitting next to a design technologist – that might not be culture, but whatever it is, it works well.

Annie and Otis. Photo courtesy: Collab

BW: Do you have a hallmark project that sticks out for you?

AL: I would say our hallmark project is Collab. Marc and I have fully immersed ourselves into understanding the needs of entrepreneurs and have developed methods and systems to grow Collab into a platform for the 21st century creative and production workforce. We are expanding. We are looking for 40,000-50,000 square feet in Manhattan or Brooklyn. Manhattan has become cost prohibitive over the past 6 years. So we’ve started to look at warehouses in Brooklyn. We plan on building out a space with enough equipment and resources to service every aspect of the creative economy. We want to continue to help start-ups, and partner with nonprofits to facilitate dynamic partnerships, combining for-profit and nonprofit initiatives and missions under one roof that can support one another as a virtuous circle.

In terms of other projects, collectively there has been some interesting work created at Collab: Brazil’s First Multi Sensory Simulation Ride, Children’s Museum of Manhattan Pop-up Book, Nickelodeon at Maker Faire, Moon by Ai Weiwei & Olafur Eliasson.

Screen shot from multisensory ride. Photo courtesy: Sensorama

BW: Does Collab represent a life philosophy - a way to look at the world of work differently?

ML: LinkedIn introduces people to one another through its platform. When you get to view and read about what someone does for a living, their profiles, you begin to connect with them. Collab takes those connections a step further, and houses them under one roof.

I would say our philosophy is in the physical expression of Collab. Connect people and give them an interesting place to work and near unlimited possibilities become achievable. What we want to do now is test our theories on a larger scale. We want to create a huge imagineering factory with tools, equipment, huge open spaces to build large installations, manufacture, host groups. Literally, a place where anything we imagine doing, we can attempt. That’s why we’re looking for a 50,000 sf warehouse type space.

BW: What’s your recipe for creative problem solving?

AL: That is so funny that you ask, because when it was just Marc and myself, we always were solving problems creatively. And at Collab, in the space, that’s something that is super natural for most of us. At Collab, if there is something that we want to invent, build, attempt, we make it.

There are almost no barriers to creativity at Collab. It’s not a judgmental place. We laugh a lot, have fun and don’t get caught up in mistakes. We try some pretty crazy things, and I think that freedom to be creative doesn’t exist as much as it should in larger companies. I’ve worked on lots of high profile projects over the years with Fortune 100 companies, and I’ve sat in conference rooms where before we’ve even named the full scope of the project, everyone is talking about the problems with the project. Naming problems is easy. It’s easy to recognize problems. It’s much more difficult to find workable solutions. I like to start meetings with clients by saying, “let’s have a discussion without using the phrase, ‘the problem is’.” I think if that phrase is taken out of the conversation, it seems to direct the conversations toward solution-based thinking instead of problem-based thinking. I know that sounds pretty corporate. But I love this type of construct. Solving complex problems that go along with big ideas instead of identifying problems is super inspiring to me.

Drone building. Photo courtesy: Collab

ML: We’ve been able to work on some very unique projects. I think creative problem solving starts with discovery. We always start projects by creating a Value Map. That’s where we rip everything apart and figure out how to approach it, name the critical elements, the most important ideas that need to be infused into the project from a Value perspective. That process creates a usable structure for the project. Creates a framework for us to be creative within a set of limitations and parameters.

Discovery and ripping things apart is what Adina does best. It is impressive for me to watch her work. She demystifies everything in that old school methodology that most MIT engineers from a bygone era used. Every engineer I’ve met over 60 years of age talks about how they used to, as kids, take their refrigerators apart. Take watches apart. And that is Adina; she takes everything apart to see how it works. That kind of approach is contagious and it’s an integral part of Collab.

AL: A lot of people in the space are like that.

BW: How do you think about and evaluate intelligent risks?

AL: That’s an interesting question. I think about it all the time. We start each project as a team and trust one another. If you don’t trust your teammates, that’s the biggest risk. We are all in it together and we can succeed because of it. And to have a really good relationship with your client, you have to be open about what the risks are. When we are working on projects we often say,” this is what you want, but here is what we are going to try to achieve” and we communicate about it throughout the project, because we want to manage expectations. A lot of times the value behind these projects goes beyond what the actual project is.

BW: Who or what inspires you?

ML: Poets. Paul Celan, William Carlos Williams, Kenneth Rexroth to name a few. Physicists like Lawrence Krause. Playing chess, playing basketball. Adina is someone who is habitually curious and inspired to the point to where she carries around this sort of MacGyver backpack with levels, drills, cameras, and tools. I love that about her. Adina inspires me.

AL: Electronics, factories, mill working, japanese design, thread, music, bookstores, tools, anything I can make something with, The Origins Project. I’m pretty much inspired by most things that lead somewhere. And of course Pippi Longstocking.

BW: What would you tell your 22-year-old self?

ML: Keep writing fiction. I stopped writing fiction when I was younger because I met a lot of really great writers, people who were 20-30 years older than me, and I started comparing my work to theirs. I came to the conclusion that there was enough good fiction out there. The world didn’t need another fiction writer. The simple answer is the world doesn’t need another anything. I would tell my 22 year old self to keep writing. If for no other reason than to engage my own imagination.

AL: I think I’d tell myself to be patient, because at 22 I was really impatient. I think it is about perspective. We see a lot of different generations in our work. I’m 45 now. I can identify with both the younger generation, but I’m old enough that I can see myself as an older person, and I like that perspective. It is interesting to me to have that perspective, especially working with technology. I actually saw an article the other day about this Founders Club that you could only be in if you are under 30. I thought that was really silly.

BW: What is one thing we wouldn’t know about you that is not in your

LinkedIn profile?

AL: Probably that I’m funny. I can be very funny. My sense of humor

isn’t apparent on my LinkedIn profile.

ML: She is very funny. She can make up songs on demand. I would say

teaching kids poetry would be my true calling.

BW: Is there anything else that I should ask that I have not thus far?

ML: We just started a women’s sewing collective where under-served women are paid a fair living wage, starting at $20 an hour, and have ownership in the company. But that’s another story for another time. Thanks a lot for your time Brett. It was nice spending time with you.

AL: It was very nice.