Austin Thomas is an artist focusing on co-created, socially engaged art. Her art making includes the co-creation of delicate constructions (aka Pocket Utopias) that promote community building and awareness, co-created sketchbooks completed in conversations and a variety of happenings in collaboration with curators, artists and galleries. Austin founded Pocket Utopia, one of Bushwick’s first artist-run galleries in 2007, which moved to the Lower East Side and then to Chelsea. You can follow Austin’s work on Instagram.

BW: Can you talk to us about your career trajectory?

AT: I moved to NYC in 1994 to go to graduate school and I immediately started working at Artists Space, which was the place to learn about emerging artists at the time. Artists Space has changed a lot and now it’s more of a kunsthalle. I think alternative spaces (and I’m not saying this in a negative way); the Drawing Center, White Columns, and Artists Space are not the alternative spaces that they were when I moved here, but that is the education that I got. I got the alternative art education by working there as an intern. I was going to NYU and I just moved here and I didn’t know which way was up and always had that feeling of trying to figure it out (this was before smartphones.) The assistant to the director asked me to balance their budget; “can you just add this up?” And I sat down with a calculator and I took my time and I added it up and I said this is not right, but here’s the right version and they said, “Oh my God somebody who can answer the phones and add!” The next day I got a call from the Director who was Claudia Gould, who is now the Director of the Jewish Museum and we are still colleagues, and she said, “Do you want a job?” And I was afraid to work there because they had fired their entire staff. And I said, “Well I’ve been in New York two weeks and a job dropped into my lap, I cannot say no.” And I knew it was going to be a hard job, 60 hours a week while being in graduate school. But I had a beautiful studio at NYU right in the East Village, a beautiful view and I spent late nights there while working at Artist Space. A lot of people from Artists Space are still my friends now twenty years later.

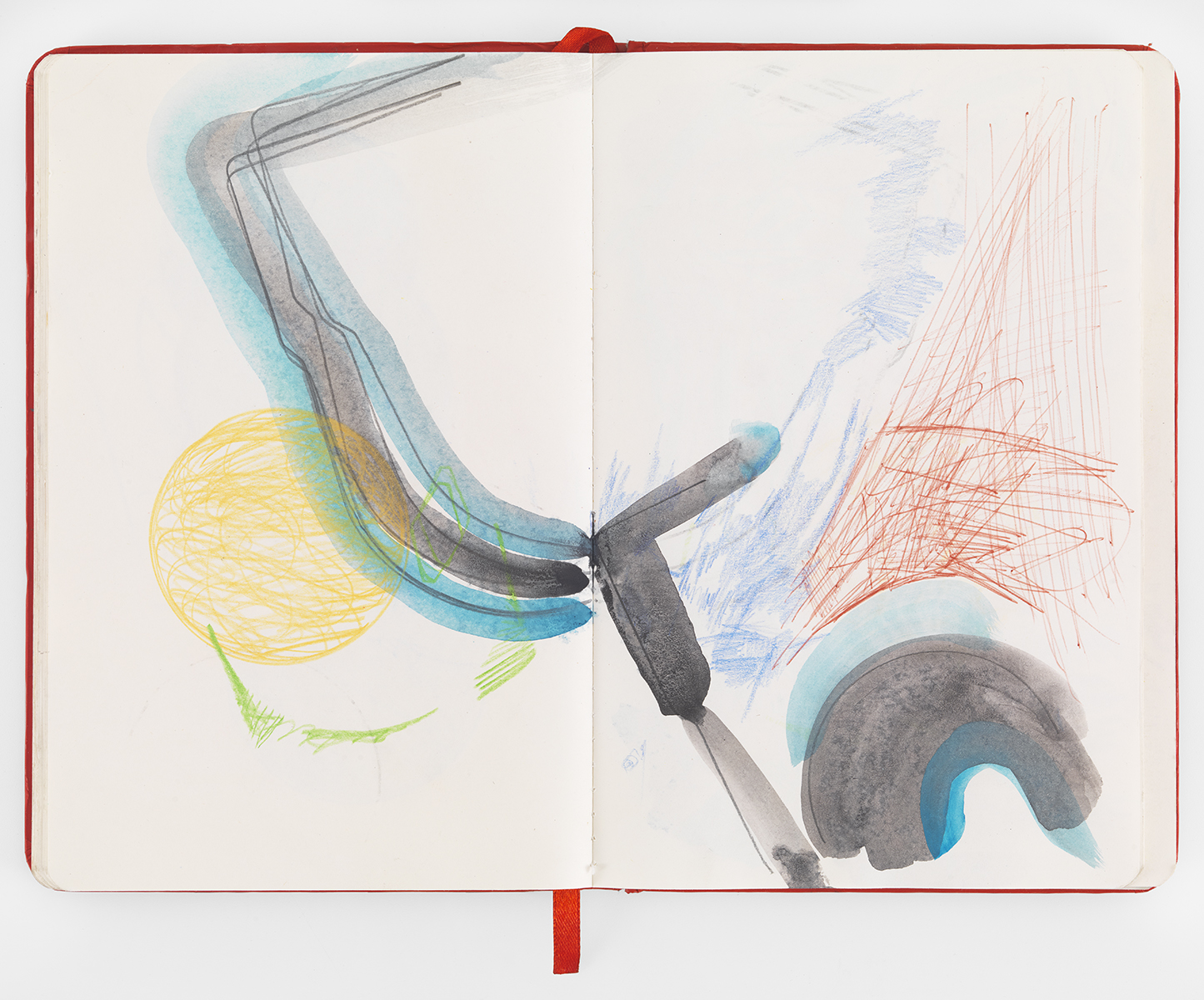

Austin Thomas, Notebook, 2015 7 x 10 inches, watercolor with pen and pencil

BW: Was that job one of your biggest breaks?

AT: That’s interesting to call it a break, it was almost like a mistake, but I met Cindy Sherman there, I met John Baldessari. I learned about Tom Marioni’s piece “The Highest Form of Art Is Drinking Beer With Friends“ (which we are doing right now) which was the first exhibition that was at Art Space when I got hired. The gallery would close at 6 o’clock and we would all get a beer and talk about art, so I would say it was influential in my way of thinking. I was educated in a DIY, artist-run way that is different from what people call artist-run galleries now. These were truly alternatives to commercial spaces.

BW: What triggered you to start Pocket Utopia? What does an artist-run space mean to you?

AT: Well, I think it’s so interesting. I started Pocket Utopia as an alternative space, (that means that it was an alternative to the main stream, which was Chelsea galleries in 2007) out here in Bushwick, for a myriad of reasons, it was an “alternative,” but at the same time it operated alongside a very vibrant art market (2007). Artists were making money, but things hadn’t exploded out here in terms of gentrification or definitely not like it is now. It was still called East Williamsburg, now it’s called Bushwick, but Pocket Utopia was an alternative space, but I think now artist-run space is just an artist-run gallery that wants a piece of the pie like a lot of galleries on the LES, but there are a lot of collaboratives like Regina Rex and I like what Julie Torres does and I applaud her DIY efforts.

I think Artist Space and my trajectory of working with artists, being an art-worker, I also worked at Harpers magazine for five years, where they really believed in putting art in the magazine as another voice. And I thought Pocket Utopia was a voice for some artists and I read something that Peter Schjeldahl wrote about art fairs 2007, when an artist goes to an art fair, they are like cows at a creamery. It was a famous quote, you can look it up, I love him, but I was infuriated by that quote, I was like, I am not a cow at a creamery! I am an art-worker. That’s what fueled the opening of Pocket Utopia, that type of activism. Pocket Utopia, was an extension of my work, a socially-engaged work of building structures that I called “perches (wooden platforms for people to converse on),” not unlike what we are doing right now.- aesthetics of the everyday .

BW: I saw a large “perch” in production to be completed next year?

AT: That perch, it’s actually finished and it’s going a few blocks from here. It’s going on Humboldt Street. It was commissioned by New York City’s Department of Cultural Affair’s Percent for Art program. When I received the commission, Sara Reisman was the Director of the Percent for Art program, who is somebody I met through Artist Space. Again, that, was the kind of spirit that Artists Space had, where there was a community. Sara Reisman now has a position as a curator and grant maker at the Rubin Foundation where she’s curating politically relevant exhibitions and continuing inspired art and activism.

Austin Thomas Plaza Perch, 2016

Stainless Steel, wood decking, acrylic panels

15’ x 11’ x 12’

Soon to be completed stainless steel gazebo-like structure, commissioned by New York City's Department of Cultural Affairs Percent for Art Program. Plaza Perch will feature a colorful acrylic trellised roof and bench for the newly built Humboldt Plaza in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn, NY along Moore Street directly in front of the Moore Street Market. Plaza Perch will be the focal point of the plaza.

BW: What first inspired you to get involved in art?

AT: Both my parents were artists. My parents met at the Greenwich Village Camera Club, they were photographers. I actually showed my mom’s work at Pocket Utopia. It was difficult, but I conceptualized her work in a contemporary context and the people of Bushwick fell in love with her. And two summers ago, when I did Camp Pocket Utopia in conjunction with Norte Maar, with Jason Andrew, my mother came and taught an art workshop. So I was born in New York, but I didn’t grow up here. I grew up on Long Island, even though they started in the city and my mom worked at magazines and my dad was a photographer. They met Richard Avedon because they met anybody who was involved in photography circa 1958-1968. They met at a restaurant called Beatrice Inn, which closed around 2004 and they met there every Monday night and they had a room to the side and they talked photography. I learned American history through my parents’ collection of photography books., I didn’t become a photographer, but now because of our phones, we are all in it. Instagram has made everyone a photographer. You were talking about your work, how you make a painting, build a sculpture, then put it through Photoshop to deconstruct and influence new work - you could just never do that a years back. My mom Kay just retired from teaching black and white photography at 80. She said no one knew how old she was and now no one teaches black and white photography.

BW: Right, my narrative and my process for making art takes account of the shift towards mass digitization along with our experiences of systems in the digital world. My work would not have been as accessible to make or discuss ten years ago.

AT: I think that’s super cool.

BW: Let’s talk about the evolution of your role in the art world.

I think that there is a different type of activism going on, which I’m struggling with now after having opened Pocket Utopia in Bushwick and having been very DIY and then opening on the Lower East Side (LES). On the LES I had this idea of trying to sustain artist careers by taking a couple of artists that I worked with here. Not necessarily Bushwick artists, because I believe art is not predicated on a location. So I moved to the LES with a very idealistic notion of sustaining a small business and my own art. On the LES I signed a ten-year lease in 2012, so I still have the lease on that space and I’ve been working behind the scenes with a variety of popups, including City Bird gallery. I encouraged them to be there for 2 years and we met every month and I helped them. But they only stayed about 10 months. I think now my role for so many artists has been as a mentor. I sort of work behind the scenes as a fairy godmother. That’s a little bit what I am doing. Maybe, because I’m old now!

BW: You also had a partnership with Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden, is that right?

AT: Actually that’s a perfect example of being a fairy godmother. Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden was a gallery and project started by Sarah Christian and Jason Vartikar right after they graduated from Harvard with degrees in environmental studies. Sarah and Jason have a real talent for looking at the interiority of art; they love the object. We were well paired. I was about social relationships, art and artists and they’re about the world and the history of objects, art history and I’m about art’s social implications. We had this brain melt of all these incredible ideas and we would all talk and talk for hours about the power of art or the object that we loved or the world it could go into, right? We kind of the came together to come apart, when they graduated from Harvard, they were 22 years old, they opened a little space in Chelsea and slept in the back and put all their resources into the space. They slept and ate in their space. They were in it to win it. They did so well that they opened another space, and like many gallerists, they might have expanded too soon. The rent got raised and they had a baby and as we know having children changes everything. I believe when you have a child, your life, and your art should change. You should be a different person. It should cause a radical change. I wouldn’t have opened Pocket Utopia if it weren’t for having a kid.

BW: What was the change that having a child inspired?

AT: Well, at the time I didn’t have a studio and I spent five days a week with my son Grant, who I love but I missed not having a studio and I missed that exchange of ideas with other artists. I am a worker, a working artist, whether working for a magazine, or at art spaces, or helping other artists facilitate their vision. I worked for Andrea Zittel and Betty Woodman. That facilitation, helping other artists with their vision, I missed that too. I wanted to talk to other artists about ideas. We bought a building out here in 2003 when I was working in a wood shop on Thames. Three of us, all friends, bought this building on Flushing Avenue and there was a barbershop on the first floor and a Chinese restaurant next door. The barbershop moved out in 2006. And my husband said, I don’t know what we are going to do; the barbershop moved out and I said I have an idea. Pocket Utopia was only open on the weekends. I spent five days with Grant and two days at my salon, as I referred to it then. Louise Bourgeois used to have salons at her house where people would come to her and Pocket Utopia was my version of a Louise Bourgeois-type salon.

I had no idea what it could become. I was desperate for community. Before I had a kid, I never sat down, I worked in my studio, I worked for other artists, I worked for magazines, I showed at White Columns, I showed at the Drawing Center, Smack Melon, I did residencies, I got commissions. I traveled with a saws-all in my purse and I really never ever sat down and then I had a kid and I had to sit! I almost lost my mind. So I said, you give me that building or I’m leaving you! My husband said all right then, here you go! I was just desperate!

BW: I think this is why your name comes up as a pioneer when I talk to folks about artist-run spaces in NYC.

AT: This is the best time ever; talking about alternative art, eating cookies and drinking beer!

BW: How did you think about the intelligent risk of opening a space?

AT: So I talked to Rico Gatson, he was the first person I told about my idea of opening up an art salon on Flushing Avenue. He also has a kid. And I think his work treads a beautiful line between art and socially relevant or activist work. We used to talk everyday. I had five people I spoke to everyday, whether at the playground, or changing diapers or whatever. I had this list of five artists I spoke to everyday. I remember I was sitting on the kitchen floor and I said time to call Rico. I said Rico, I think I might open a gallery and he said, “Do it…when are you going to show my work!” Then I told my mother, I think I’m going to open a space. I borrowed money from her to renovate. I paid her back. But as soon as I took that loan, she said, “When are you going to show my work?” I guess all of us artists, we live for an audience, we are nothing without an audience. I think I fell into making socially engaged work by accident, making things that people could use, or relate to, or commune with or be with. Pocket Utopia was kind of an accident.

BW: Was there anything that really stuck out to you as kind of a magic moment or a turning point in your career?

AT: That’s an amazing question. Well, I showed at Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden in 2014 before we merged and that show was very significant to me because Sarah and Jason asked me in their young, fresh, Harvard-educated-ness to leave Pocket Utopia empty on the LES. I was running Pocket Utopia on Henry Street then. So I had to rearrange the exhibition schedule and I said, “Why empty?” And they said, “Because Pocket Utopia is your artwork and we want to showcase it, in addition to showing your work or objects here in our gallery in Chelsea, we want to show Pocket Utopia. It was really the first time I saw Pocket Utopia as an art piece. But I programmed Pocket Utopia with a series of “happenings” that were very much reminiscent of the Bushwick days. So on the LES we played bingo, held potlucks, discussions; it was a very intense six weeks! I even introduced a Pocket Utopia scent and Ben Godward, a Bushwick artist, actually won a solo show at Pocket Utopia in a crazy bingo game one night. I feel like I still owe him. Then Pocket Utopia merged with Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden. We just really got along, our ideas meshed. Sarah and Jason were the first ones to make the connection that Pocket Utopia was an artwork.

BW: How do you describe your work?

AT: I think of art making as not necessarily a practice. I like to use that words art making. I draw everyday, but I draw with a group of other people so I feel like I’m drawing conversation. I always have my sketchbooks with me. Every morning after I take my son to school, I go and hang out with other moms and draw. They are not artists, but they have embraced me and they allow me to do my thing, I can’t do my thing, drawing in my sketchbooks without them because they are talking and I am drawing their conversation. It’s socially engaged, now my kid’s eleven and he’s in sixth grade and we’ve been at this school since second grade and I’ve been drawing since second grade in sketchbooks. I couldn’t draw without the moms talking. My son’s been sick for two days and I’m miserable and the moms are miserable because they don’t have that artist drawing, it’s a co-creative process of communication. I just got a new type of sketchbook, which gets scanned when it’s finished, you send it back into the company and they scan it, but I haven’t done it yet. Soon!

Austin Thomas, Notebook, 2015 7 x 10 inches, watercolor with pen and pencil

BW: Where could one view these sketchbooks?

AT: I put them on Instagram. I feel like, for a parent, when you are home with the kid, there is nothing like the Internet! Even the other day, I was at the amazing Newark Art Museum, looking at work with the curator, and I said, “Where’d you find this artist?” And she said, “The Internet.” Which was kind of refreshing it was not at an art fair.

BW: Could you share some insight into the multiple art worlds that we see today?

AT: On a good day, on any one block in New York, in an art neighborhood, there can about ten different art worlds. There are more dominant art worlds, made that way due in part to real estate prices and those constraints. Hansel and Gretel Picture Garden Pocket Utopia closed because the rent was too high. We felt like we could do better by ourselves or by breaking it up into small, more interesting parts; including creating residencies, making new work and coming back to Bushwick to this public piece. And I mentioned that I’m working on or sort of managing that lease on the LES. Sarah and Jason, of the former Hansel and Gretel Picture are out in New Jersey doing a residency because that’s where they live. Market forces can beat you down and I think as artists, we have to find ways whether it’s through Instagram or where ever to still be activists, to still influence culture in a radical way. I think it is our job still to envision the world that we want our work to go into, not just how to make work to relate to a market or a fair. I’m not opposed to the market and I’m not opposed to fairs, I still think we need to be visionary. Your studio is visionary, you’re still in a raw space, in here with other artists in Bushwick. At the end of the day we’re all artists. I think my moms, those that I draw with, are really artists too. Well, they are definitely my muses.

BW: New York is a really challenging place right now to be an artist, is it still doable?

AT: I think it’s still doable. I am looking for a studio space now. I got off the subway here in Bushwick and it’s amazing all those murals. They are amazing, right? I recently spent some time in Nashville. I meet a lot of artists that are graduating from art schools, like the Art Institute of Chicago and are moving to Nashville. It’s great., but there are no collectors there. My thing is every artist should buy other artists’ artwork and collect art. I feel like if you are going to be an artist you should participate in all the processes. You should write, you should curate, you should collect, and I’ve sort of done all those things.

BW: What is your advice to emerging artist professionals?

AT: I think it’s a combination of things; you can’t underestimate your online presence and that you should participate in all the aspects of the art world. For instance, if you think you want collectors to buy your work, then you should be a collector. Participate.

BW: I don’t think I have ever heard that before – the part on collecting too.

AT: I funded the first Pocket Utopia out of my own art collection. No one realizes that, but I sold my John Baldessari and my Cindy Sherman to fund the Bushwick Pocket Utopia. You have to have a vision. I’ve bought things for $500 and they’ve then sold for $3000. And all of my collectors who bought my work, bought the artists work that I showed at Pocket Utopia. I shared.

BW: What do you think needs to change in the art world now?

AT: I miss the alternative spaces, I miss Artists Space, I miss White Columns, the way it used to be, I miss the Drawing Center. Now instead of going to alternative spaces, I maintain memberships at MOMA, the Whitney, and I just bought a membership to the Newark Art Museum. I’ve embraced the institution. Thankfully the studio visit is still alive and well.

BW: What inspired the gallery’s move to Newark and how do you like it?

AT: It’s very close to here. It takes me the same amount of time to get to Newark from my house on 16th Street as it does to get to Bushwick. Rebecca Jampol invited me to come to Newark when Pocket Utopia/Hansel and Gretel Picture Gallery closed in Chelsea. Newark is very close to New York City and I really respect Rebecca and what she is doing there. She has taken over three floors of an office building. So it’s a different gentrification or repurposing because businesses have left. It’s an empty office space. Rebecca has 55 studios at the Gateway Project and I’m one of them and I’m calling it Post Pocket Utopia. I don’t know what’s going to happen there. I started with a show called “Seeing Newark,” it’s a crowd sourced show. Newark happens to have a huge street photography movement, people shoot things off the street and there are a cadre of individuals who have been photographing Newark for like ten years and one of them does an amazing magazine called Hycide. So, “Seeing Newark,“ is a photo exhibition of Newark but anyone can participate by using the hashtag #seeingnewark and posting an image online. But Newark is not a private place where I make art. That’s why I rented this tiny space right off the Lorimer Stop. I’m so excited to be alone with my ideas and near where my public piece is going to be placed. I can expand in the studio and in the public realm I need to be alone with certain ideas and I need to activate other ideas in public or be socially engaged. I really believe in ideation, I need to cut and paste and just think. Make collages, notes.

I don’t know what’s going to happen in Newark, it’s exciting, there’s a lot of potential there. Artists go where there are cracks in the sidewalk, that’s why I came out to Bushwick originally.

New Studio in Williamsburg

BW: What is the best advice that you have ever received?

AT: That’s a good question. Ok, Betty Woodman always said, “Leave the dishes, do your work.” Andrea Zittel said, “Leave every place better than you found it.” I think that’s good advice, in that world-making way. I feel like artists don’t have a clue about the economy, how creative economy works. For instance, Warhol was instrumental in creating a cultural economy in New York. Even now the Warhol Foundation is still thriving and supporting the arts. I guess advice I would give to other artists is that find people that you can collaborate with, I believe in co-creating. And we all need time in our studios. So you have to value that time alone as well as putting your work out there.

BW: What is a question you wish you got more often?

AT: I guess people don’t necessarily see Pocket Utopia as related to my artwork. When I sell an artist’s work or when I show other artists work whether it was here in Bushwick or on the LES or in Chelsea, my own art became secondary. I don’t embrace that type of hierarchy. There is a naiveté about artists, who don’t want to be labeled, but they will label you as a gallerist. I like the term “gallerartist,” something the artist Carl Ferrero coined for me while we were at the Millay Colony. Many artists run galleries and that term should be used more. Leslie Tonkonow, she’s been in business for a really long time, I have a huge amount of respect for her gallery. She was an artist. She didn’t think, I’m going to open a gallery and make a lot of money. She was a performance artist doing crazy stuff in the East Village and she evolved into running a gallery, now she’s really dedicated to her artist’s careers. She’s a little old school in terms of half her time she says she dedicates to building artist’s careers. Amazing! She’s super interesting. She inspires me.

BW: How do you measure success?

AT: I believe in the silhouette. When somebody dies, people often talk about his or her stature, like they built this and formed that and were a part of this organization. I really believe as a human being or an artist, that it’s not about your stature, it’s about your silhouette, the shadow that you cast. On a day-to-day basis, there is so much that I do for my own art and for other artists. Or I might facilitate an uplifting sort of experience for someone. I want to cast a very long shadow and it’s not about my name or whom I’m with. I’m going to make artwork no matter what. Nothing is going to stop me from making art. I love other artists; I believe in other artists, I believe in art. Art has enriched my life.